Avaliação do possível papel do acaso em testes imparciais

papel do acaso pode levar-nos a cometer dois tipos de erros quando interpretamos os resultados de comparações imparciais de tratamentos: podemos concluir erradamente que existem diferenças reais nos resultados quando elas realmente não existem, ou que não existem diferenças quando, na verdade, elas existem. Quanto maior o número de resultados de interesse dos tratamentos observados, menor será a probabilidade de nos enganarmos dessas maneiras.

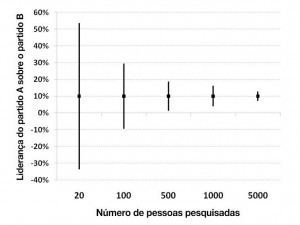

Como as comparações dos tratamentos não podem incluir todas as pessoas com a condição que foram ou serão tratadas, jamais será possível descobrir definitivamente “as diferenças reais” entre tratamentos. No entanto, os estudos têm de produzir as melhores hipóteses do que as diferenças reais provavelmente são. A confiabilidade das diferenças estimadas é muitas vezes indicada por intervalos de confiança (IC), que fornecem uma variação na qual as diferenças reais podem estar. A maioria das pessoas já conhece o conceito dos IC, mesmo que não seja por esse nome. Por exemplo, na corrida eleitoral, uma pesquisa de opinião pode relatar que o Partido A tem uma vantagem de 10% de pontos sobre o Partido B. No entanto, depois o relatório apontará que muitas vezes a diferença entre os partidos poderia ser tão pequena quanto 5 pontos ou tão grande quanto 15 pontos. Esse IC indica que a diferença real entre os partidos pode estar entre 5 e 15% dos pontos. Quanto maior

o número de pessoas entrevistadas, menor será a incerteza sobre os resultados, e, por isso, o IC associado à estimativa da diferença será menor.

O Intervalo de confiança (IC) de 95% da diferença entre o Partido A e o Partido B encurta conforme aumenta o número de pessoas sondadas

Assim como é possível avaliar o grau de incerteza ao redor de uma diferença estimada nas proporções dos eleitores que apoiam dois partidos políticos, também é possível avaliar o grau de incerteza ao redor de uma diferença estimada nas proporções de pacientes que melhoram ou pioram após dois tratamentos. E aqui, mais uma vez, quanto maior o número dos resultados do tratamento observado – p.ex., recuperação após um ataque cardíaco – em uma comparação de dois tratamentos, menores serão os IC que circundam as estimativas das diferenças do tratamento. Com relação aos IC, “quanto menor,

melhor”.

Um IC é normalmente acompanhado por uma indicação do nível de confiança que podemos ter de que o valor real reside dentro da gama das estimativas apresentadas. IC de 95%, por exemplo, indica que podemos confiar 95% no valor real de qualquer coisa estimada dentro da gama do IC. Isso significa que existe uma chance de 5 em 100 (5%) de que, efetivamente, o valor “real” esteja fora do intervalo.